Flood buyout program managers need to give property owners information and support, not just money, says expert

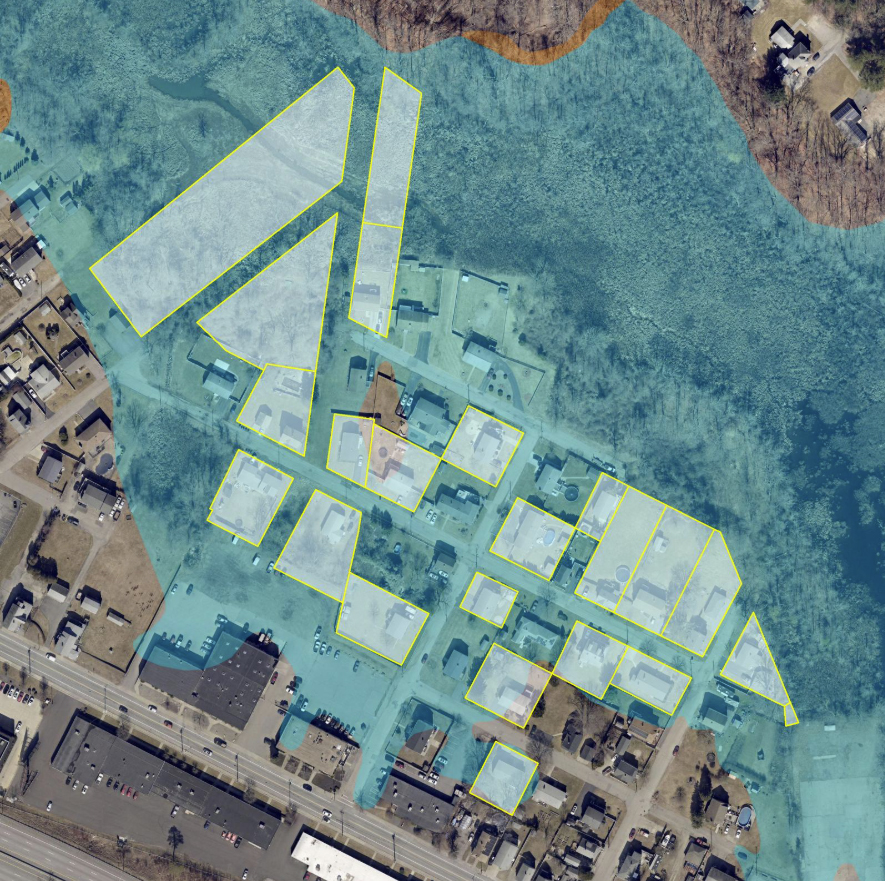

These homes in East Providence near the Runnins River were the site of frequent storm flooding. In partnership with the Northern Rhode Island Conservation District and the city of East Providence, the NRCS Emergency Watershed Protection Program funded a buyout of 13 homes and 5 vacant lots in this neighborhood. Photo by Dyan Sierra courtesy of NRCS.

The prospect of selling your property—not to another family to raise their children in, but to a government program so that it can be demolished—is difficult, beyond the logistics of paperwork, market value, and wait times.

Gina DeMarco, special projects manager with the Northern Rhode Island Conservation District (NRICD), works on buyout programs for flood-prone areas in Rhode Island. She explained the technical details in a webinar for municipal planners and others in the Rhode Island Climate Resilience Learning Network (RICRLN). For instance, one federal program covers 100% of the costs, but takes years—decades—to implement. The other requires a 25% match from a municipality, but is able to respond more rapidly to a flooding event.

But DeMarco wanted to be sure her listeners understood the nuances of the programs as well.

“Having that one person, whether it be the district or the municipality, there’s a friendly, consistent face. It’s good to keep one person… that people begin to know and trust,” she said “They know that they can call them with any questions as they go through the process.”

And homeowners participating in voluntary buyout programs offered by the Natural Resources Conservation Service (NRCS) have a lot of questions.

The map illustrates the properties acquired as part of the voluntary buyout in East Providence. The highlighted areas without buildings show land purchased as a floodplain easement. Image courtesy of NRCS.

The buyout programs have properties appraised and then offer fair-market value to the owners. But deciding to accept the offer can be difficult, DeMarco said.

“Keep in mind that [what] homeowners are considering is that even though we’re providing the fair market value, the market here in Rhode Island is extremely competitive. So can they find a new home? If they do, can they afford it? Because some of them have 2 and 3% interest rates, and even though interest rates are starting to go down a little bit now, it’s still quite a bit more to borrow money. Others that are thinking they don’t want to sell, and are worried about what the neighborhood is going to look like if they stay,” she said. Elderly residents have to decide “does it make sense for me now to make that move to a condo or to a nursing home facility, or to move in with a relative?”

DeMarco described a recent project at a neighborhood in East Providence, which received $7 million from the NRCS through the Emergency Watershed Protection Program, which requires a 25% match from the municipality. Eighteen properties were purchased.

“During the period from 2018 to 2022 there were four major floods right in this neighborhood,” DeMarco said. “It’s almost an annual event.”

The funding was authorized following Tropical Storm Ida in 2022, and the properties were purchased at fair market value and transferred to the city of East Providence, DeMarco said. She added that the fair market value was assessed “as if the flood had not occurred.”

The easements on the purchased properties are held by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management in perpetuity, with no development allowed, though the city can use the land for passive recreation, like walking trails, she said.

The Pocasset River floods portions of the town of Johnston and the city of Cranston on a regular basis. Photo courtesy of NRCS.

While the NRICD hosts informational sessions to educate property owners as the buyout programs launch, DeMarco also cautioned that it is important to manage homeowners’ expectations as the process goes on.

“Theoretically, you could start and end this project within six to nine months, if everything went smoothly all along the way. But I guarantee it will not. And people keep calling you and saying, ‘Well, when am I going to get my appraisal? When am I going to get this? When will I get that?’” she said. “And so out of mercy, you usually say, ‘Well, I don’t think it’s going to be more than a month,’ but then it is more than a month, so it’s just really hard.”

Despite those challenges, DeMarco said, the buyout programs offer a range of benefits, not only to homeowners, who can move out of properties that in many cases have flooded multiple times, but also to communities.

In the East Providence program, NRICD offered the opportunity to nonprofits in the state involved with housing issues to salvage materials from the houses that had been bought out and were going to be demolished. Habitat for Humanity responded, DeMarco said, and was able to remove windows, doors, appliances, and other items from the homes to use in their housing projects or to sell at their ReStore stores to raise money for their program.

First responders were also able to use the homes for training in ways that more accurately reflected real-life conditions, DeMarco said. “They usually work doing their training in, like a warehouse or something. So to actually have homes, they were just very, very happy to have that opportunity, and I was happy to be able to use the properties to the best of our ability.”

Most importantly, the homes are removed from the floodplain to allow for more absorption of floodwater.

One webinar participant wondered whether municipalities were concerned about losing these properties from the tax rolls. DeMarco answered that “there was some concern at the beginning when we were talking with the municipalities, but they have quickly gotten past that, and they realized that … it’s cost effective for them to lose that [revenue] as opposed to responding to the flood issues.”

Another asked about relocation assistance. While the owner of the property receives the fair market value of the home “If there are other adults living in the property,” DeMarco said, “they are offered a financial allotment of money for relocation.”

After the webinar, participants surveyed noted that while they were broadly aware of NRCS’s property acquisition program for flood-prone areas, they valued the chance to get a more “in-depth look at the requirements, process, and considerations associated with these programs.”

Eliza Berry, coastal project manager for the URI Coastal Resources Center and Rhode Island Sea Grant, leads the RICRLN. Contact her at eliza.berry@uri.edu.

In the future, participants would like to learn about approaches to engaging residents in these sensitive conversations around buyouts. Leaders of the RICRLN are planning future programs that respond to these needs.

This webinar was sponsored by the Rhode Island Climate Resilience Learning Network, a project of Rhode Island Sea Grant, the URI Coastal Resources Center, and the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve.

Related Links:

- Join the RICRLN

- Rhode Island Disaster Recovery (NRCS)

- Managing “Managed Retreat” – story on Exploring Managed Retreat: Pathways to Community-Led Resilience Workshop with links to presentations and resources

- Pocasset River Buyback Program for Flood-Prone Homes Closes on First Properties (ecoRI)