Recovery of benthic ecosystems point to improved environmental conditions from upgrades in wastewater treatment

Estuary ecosystems are some of the most complex where freshwater meets saltwater, creating a mosaic of habitats essential for commerce, recreation, and fishing. These ecosystems have adapted to this duality, but how they have and will respond to changes in activities along the coast, rising seas, and warming temperatures is unknown.

With improvements in wastewater treatment facilities and storm runoff management, Rhode Island has been able to exceed its goal of a 50% reduction of nitrogen input into the Narragansett Bay, resulting in marked improvements to water quality. Now, scientists have evidence that these efforts are improving biological communities.

“We know the nutrient input has decreased and water quality has improved in the upper bay, but this is one of the first pieces of evidence that the nutrient reduction has resulted in a direct effect on the biological communities, which has been very difficult to demonstrate,” said Dr. Jeremey Collie, professor of oceanography at the University of Rhode Island’s Graduate School of Oceanography.

Collie was joined by his former student Shaina Harkins, a graduate of URI, and Heather Kinney, a coastal restoration scientist from The Nature Conservancy, to discuss these findings during a recent Coastal State Discussion webinar hosted by Rhode Island Sea Grant.

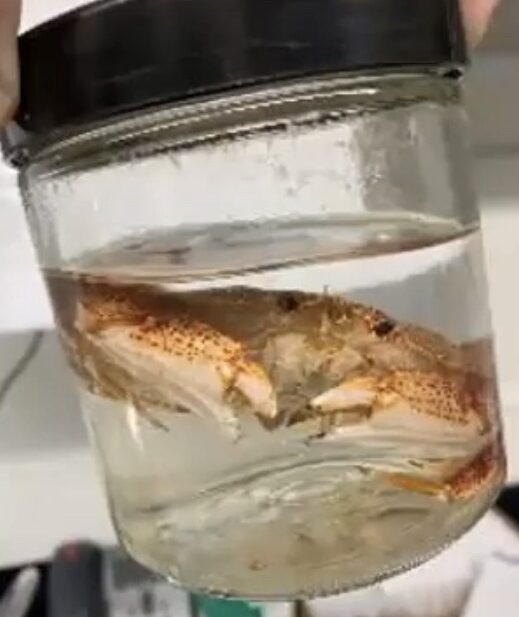

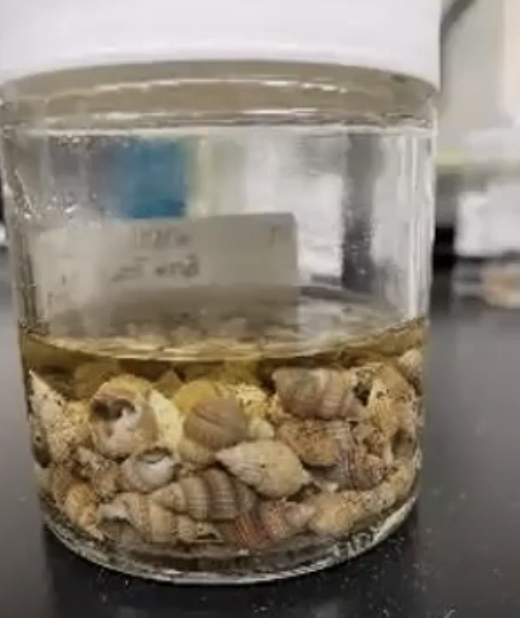

To understand how the bay is changing, researchers like Collie, Harkins, and Kinney are looking to “benthos”– benthic ecosystems that reside at the surface of the sediment (such as mollusks, crabs, or fish) to below (such as shellfish and burrowing worms known as polychaetes). These communities are a critical foundation for the marine food web, act as nurseries for many species, and are subjected to legacy pollutants like nutrients or heavy metals, which can alter oxygen levels within the sediment.

Results from Collie and Harkin’s work showed the benthic community in the upper bay has become more similar to the mid-bay around Jamestown over time, suggesting an increased successional stage. This means that they’re finding species that are larger, longer-lived, and reside below the surface, which is indicative of improved oxygen conditions. It also means a more resilient and stable ecosystem that has a wide-range of benefits for both the environment and varied uses of those resources.

“Generally, you’re looking at high abundance, short-lived, opportunistic species in a low successional area … in a high successional area, you’re seeing larger, longer-lived, less abundant, and deeper dwelling organisms like bivalves [such as quahogs], which will result in seeing the same organisms year-to-year instead of a shuffling of larvae settlement from different species,” explained Harkins, who likened this process to how a forest rebuilds after a wildfire in which various species resettle over time until it becomes a mature forest again.

Although their study was limited to three sample sites, making it difficult to generalize the conditions of the benthic system across the bay, Collie pointed to Kinney’s work with The Nature Conservancy as a complementary project that focused on the upper bay and Providence River estuary using valuable imagery methods to better understand these environments where the impacts of nutrient reduction efforts will likely be most acute.

“We had three main objectives with similar overlap,” said Kinney, who described their process using a variety of imagery methods in order to build a baseline for comparison with historical data.

Analysis of the various image sets from TNC are still ongoing that will be used, along with Collie and Harkin’s work, to build a more complete baseline on changes in Narragansett Bay’s benthos that has long been lacking and to more accurately answer the question of whether Narragansett Bay is improving after large public investments in treatment facilities to informs adaptive management moving forward.

The Coastal State Discussion Series is a forum dedicated to highlighting current scientific research focused on marine issues impacting Rhode Island coastal communities and environments.