Some Massachusetts emergency shellfish harvest closures could be overly strict; Rhode Island uses other management tools to protect consumers while avoiding harm to industry, Marine Affairs Institute/Rhode Island Sea Grant Legal Program research finds

Some Massachusetts emergency shellfish harvest closures could be overly strict; Rhode Island uses other management tools to protect consumers while avoiding harm to industry, Marine Affairs Institute/Rhode Island Sea Grant Legal Program research finds

Buzzards Bay oyster farms were closed to harvesting for 210 days last year due to precipitation that led to combined sewer overflows (CSOs) in the bay. But were the oysters really unsafe to eat?

Dale Leavitt, who owns one of the affected farms and formerly taught aquaculture at Roger Williams University, argues that they were safe, and that rules that automatically close areas of a waterbody to shellfish harvesting after a certain amount of precipitation may be excessive and harm shellfish growers.

His farm, he said, is in “an enclosed embayment that has a certain level of restrictions in terms of water flowing in and out, which is good for us, because it means that the stuff coming out of New Bedford is restricted in terms of how it gets into our bay … We have never, ever tested above the threshold level [for contamination]. We’ve not even come close to the threshold level.”

Leavitt, who is on the shellfish advisory panel for the Massachusetts Division of Marine Fisheries (DMF) as well as Joshua Reitsma and Matthew Charette of Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute Sea Grant, approached the Marine Affairs Institute (MAI)/Rhode Island Sea Grant Legal Program at Roger Williams University School of Law to request help pursuing legal research to see if there were other ways to manage the harvesting of shellfish in a way that would protect public health without unnecessarily closing shellfishing areas for days at a time.

The implications are significant. Oysters are the third most valuable shellfish harvested in Massachusetts after scallops and lobsters, Seth Garfield, president of the Massachusetts Aquaculture Association said.

Oyster growers “employ over 1,000 people … So there’s lots of money involved. The gate value, I think we produce 50 million oysters, and the gate value is approaching $40 million, so it’s a big deal.”

Alexandra Tamburrino, MAI staff attorney, took on the research, and found that Rhode Island has a model that Massachusetts could adopt that takes localized factors into consideration in determining when shellfish harvesting areas need to be closed.

Alexandra Tamburrino discusses how Massachusetts could follow Rhode Island’s lead in using a Conditional Area Management Plan, or CAMP, to refine its approach to shellfish harvest closures.

In a presentation of her research at the law school, she explained that Massachusetts has adopted the model ordinance for shellfish sanitation offered by the National Shellfish Sanitation Program, which includes provisions for emergency closures. These are triggered when an area that is normally clean and safe for shellfish is contaminated by an event such as rainfall that causes combined sewer systems to overflow and discharge untreated wastewater into bodies of water in proximity to shellfish growing areas.

Using only distance from the outfall as a measurement, however, fails to take into account localized conditions that can make a difference in whether shellfish are actually contaminated by the pathogens contained in wastewater. These include many factors. One is water temperature, which affects the rate at which shellfish filter water, and therefore expel pathogens. For example, in the summer, oysters are more active and depurate more quickly. Guidance from the Interstate Shellfish Sanitation Conference (ISSC), Tamburrino said, “notes that evidence from different field studies has indicated that a constant relationship doesn’t exist between the [pathogen] levels in shellfish, and the presence of these contaminants in the actual waterbody itself.”

To take a more refined approach, Tamburrino said, growers or other interested parties could submit a proposal to the ISSC, which meets every two years (next in October 2025), and the issue could be assigned to a task force for review. Massachusetts growers could also approach the DMF’s Shellfish Advisory Panel and provide it with unbiased research to make a case for a change.

Tamburrino suggested that a different approach might be more effective.

Waters that are open to shellfish harvesting but may be closed due to events such as CSOs are classified as conditionally approved or restricted areas. Rather than using the broad emergency closure approach, which looks only at rainfall, Massachusetts could create Conditional Area Management Plans (CAMP) for the impacted areas.

Tamburrino said these plans are “created using localized and growing-area-specific data. This provides ample discretion for the regulating authority and the harvesters to work together to delineate closure standards and reopening standards that take into account all of those factors … whether it be the species of the shellfish, the water temperature, the shellfish activity, cleansing rates, presence of silt and chemicals that could interfere with the shellfish activity.”

An updated CAMP for already conditionally approved areas can incorporate a CSO condition that includes growing-area-specific considerations, such as distance from a CSO, specific rainfall metrics, and more, Tamburrino said.

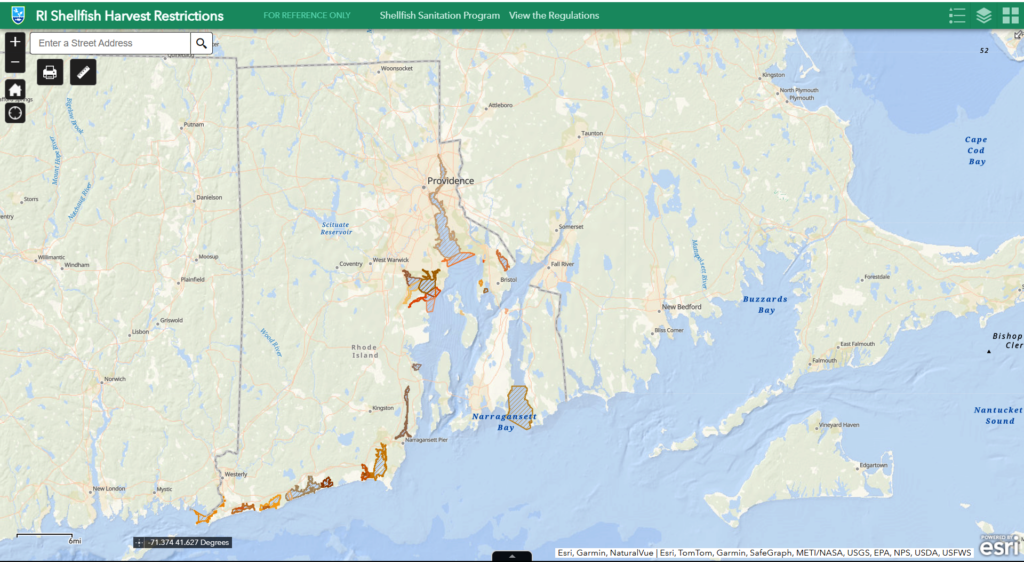

Rhode Island has used this approach in the Providence River, which had been classified as prohibited prior to CSO improvements. Now portions of the river are classified as conditionally approved with a CAMP based on data, despite some remaining CSO inputs.

“The Providence River CAMP contains conditional criteria and closures for reopening based on both treatment plant operation and precipitation,” Tamburrino said, and added that the criteria are “based on 452 fecal coliform samples taken during both dry and wet weather” that demonstrate the growing area has met the NSSP criteria for conditionally approved waters. This, she said, is an example of how “tailoring the growing-area-specific closures can protect both the public health and the industry.”

After Tamburrino’s presentation, Leavitt said that he was pleased to learn about the possibility of using a CAMP for the area his farm is in. He said that the Massachusetts DMF has been cooperative in working with the industry and has provided fecal coliform data going back to 1984.

“We are in the process of doing a side-by-side analysis of fecal coliform levels versus rainfall for the last 30 to 40 years, hoping that that information, because it’s coming out of the DMF lab, will allow us to submit that data for working primarily—to at least in my mind—through a CAMP.”

“The fact that we have your diligence to do this in a timely way, to present it to the SAP meeting … hopefully the Director of the Division of Marine Fisheries can say, ‘Somebody just did my homework for me,’” Garfield said. “This is fantastic.”

Tamburrino’s research will be available in a report, “Shellfish and CSOs: Emergency Harvest Closures Under State and Federal Law,” on the Marine Affairs Institute website.

The Rhode Island Sea Grant Legal Program is a partnership between Rhode Island Sea Grant and the Marine Affairs Institute at Roger Williams University School of Law.

—Monica Allard Cox, Communications Director