By Meredith Haas

Contributions by Allie Shinskey

Retreat. Accommodate. Protect. Attack.

These are common phrases used for adaptation and mitigation efforts in the “war on climate change.” But does this militaristic approach result in more conflict that hinders real solutions?

“I realized this language is very militarized and combative. We always want to fight or combat climate change,” said Dr. Kelsey Leonard, an assistant professor in the Faculty of Environment at the University of Waterloo, during the first University of Rhode Island’s Honors Colloquium, “Sustaining Our Shores.”

As an enrolled citizen of the Shinnecock Nation, which lies at the east end of Long Island, Leonard’s research focuses on Indigenous water justice, and she spoke about humanity’s relationship with the coast and issues of climate change.

Dr. Kelsey Leonard

“Maybe we could think of more hopeful language … language that inspires us to care, to steward, to be responsible,” she said. “Additionally, I didn’t see any cultural connection with these principles that would align with the cultural ideologies of tribes in New England and in our region.”

The generic sea level rise adaptation framework from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), Leonard notes, not only uses militaristic language but reflects western scientific and cultural biases reflected in limited adaptation options.

“The designs for these adaptation measures are a very western structure of a home. A box square and, triangle roof … houses in Vietnam aren’t made like this; neither are all Indigenous houses,” she said, explaining that climate change affects everyone and more people would think about adaptation if more thought was put into the design and communication, especially as Indigenous peoples feel these affects more acutely.

“As tribal nations, like mine of Shinnecock, we could have permanent inundation loss of land to water or wetland migration. The land isn’t going anywhere. These ecosystems are thriving and creating new types wetlands and useful spaces … but the impact for tribes that have very limited land resources, it reduces our access to those lands for other means of living.”

This includes distinct challenges to water security given the increasing threats of sea level rise. Leonard pointed to a satellite image of her home territory by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) that showed massive inundation by 2050 at the low range of 0.7 to 2 feet of sea level rise estimations. By 2100, she said, half of the Shinnecock reservation will be inundated.

“It might not be in my lifetime, but it will be in the lifetime of my children and grandchildren, and it’s not like we have somewhere else to move,” Leonard, explaining that while the effects of climate change impact everyone, they don’t do so equally.

Climate change, she said, has “varying implications for different communities, [and] it also raises questions about ocean justice, which is concerned with the disproportionate types of burdens that are placed on certain communities over others and the disproportionate types of benefits received by some communities over others … We shouldn’t only be thinking about who bears the brunt of these impacts, but who gets the benefit when we do take care of it.”

More inclusive and effective adaptation design, Leonard said, could incorporate Indigenous values. “We can be solutions-oriented and find a path that allows us to coexist, to learn from one another, and to grow together.”

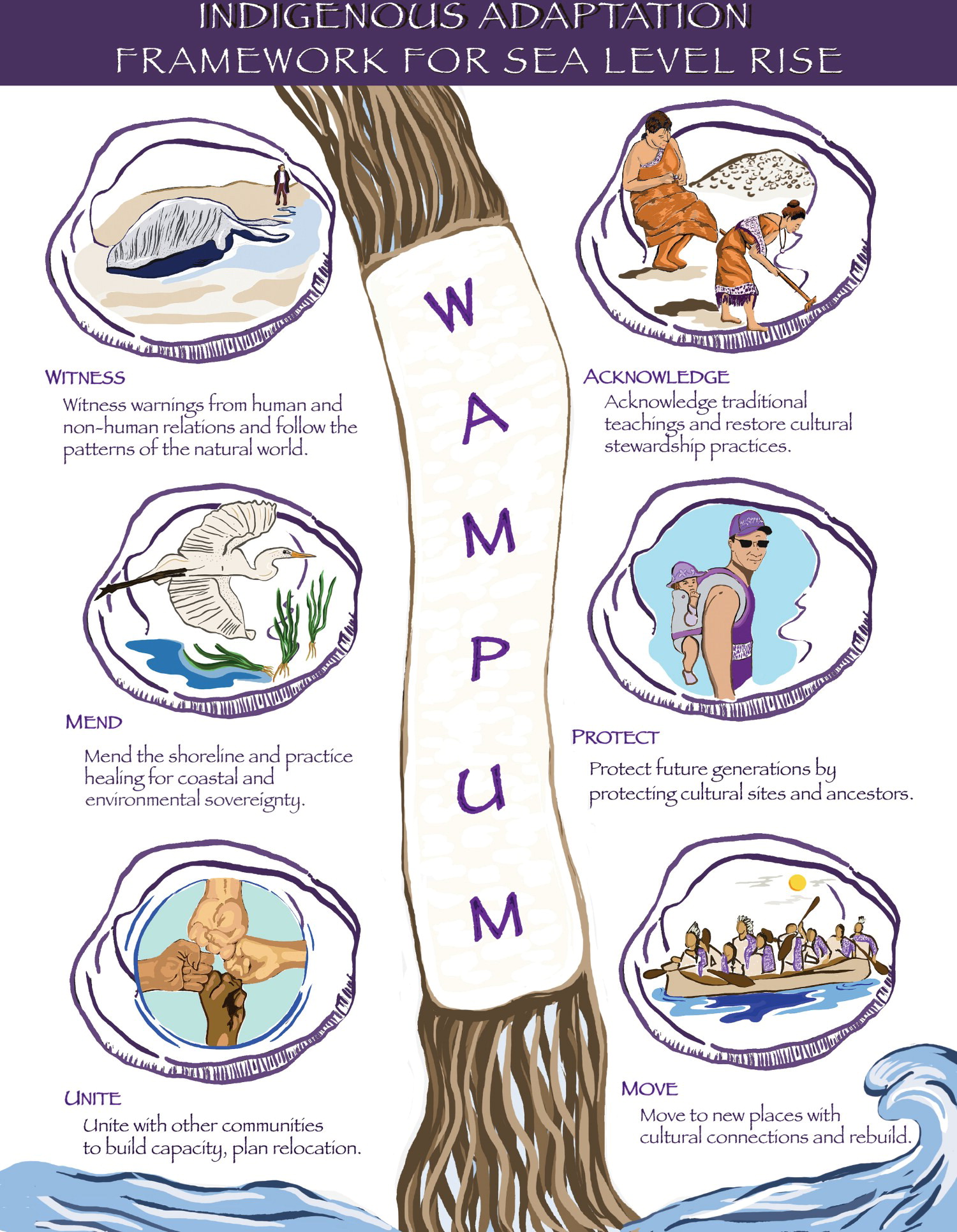

To achieve this, Leonard has been working with tribal nations throughout the region to develop a WAMPUM adaptation framework that incorporates existing resilience activities of Indigenous peoples in the Northeast.

“As Shinnecock people and Narragansett people, we are people of the sea. We are wampum makers … from quahog and whelk shells, and we are master carvers of those shells and harvesters … which we’ve been doing for thousands of years. [This] is important in the context of sea level rise and climate change adaptation because we have a millennia of knowledge in this part of the world in adapting to rising seas and in understanding our changing landscapes and seascapes.”

To imagine what sea level rise adaptation would look like if it was designed with Indigenous values, she said, is to be critical of how we, as humans, understand our presence in the environment.

“We have seen increasing, unusual mortality events of whale relatives [humpback and right] since 2016 along the Atlantic coast … we have a unique relationship as Indigenous people of this coastline with those beings. They are here, they are telling us something: that we need to change the way we are responding to climate changes, to be a witness to those messages and to be able to learn from them and adapt.”

Leonard emphasized the importance of Indigenous knowledge and teachings in order to restore cultural stewardship practices and prioritize nature-based solutions. The biggest challenge, however, for integrating this framework is support.

“We don’t have many strong allies on the East Coast that want to see tribes succeed,” said Leonard. “If we had more allies, we’d see more of these activities.”