Looking out from the University of Rhode Island’s Bay Campus in Narragansett, the waters of Rhode Island Sound and Narragansett Bay stretch toward the horizon, carrying fishing boats, ferries, and research vessels through the same channels. It was here on this shoreline that the Graduate School of Oceanography (GSO) took root in the early 1960s—and where its founding dean, Dr. John A. Knauss, helped shape not only a world-class institution but also a national vision for the ocean that included the National Sea Grant College Program.

I believe the oceans and the 70 percent of the Earth that is underwater will play an increasingly important role

Dr. John A. Knauss, founder of URI Graduate School of Oceanography, co-founder of the National Sea Grant, former Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere in the Department of Commerce, Administrator of NOAA, president of the American Geophysical Union, and a delegate to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

Born on September 1, 1925, in Detroit, Michigan, Knauss was a physical oceanographer whose career coincided with America’s growing interest in the sea. In the wake of World War II, the U.S. Navy recognized the importance of understanding the ocean. At the same time, scientists and policymakers began to see it as both a vital natural environment and a resource.

Expanding economic activity in the coastal zone during the 1960s, along with a drive for U.S. competitiveness in science and growing environmental awareness, underscored the need for national policy on fisheries, coastal zone management, and ocean resources.

Knauss served as an ensign in the U.S. Navy in 1946 and later worked with the Office of Naval Research, where he lobbied for partnerships between the Navy and universities to advance oceanographic research. This work led him to pursue his Ph.D. at the Scripps Institution of Oceanography before arriving in Rhode Island to help establish GSO in 1961.

When he arrived, oceanography was still a young field, but Knauss believed that science should serve society—a conviction that became central to the National Sea Grant College Program. Modeled after the Land Grant university system that had long connected agricultural research to the public good, Sea Grant was designed to link marine and coastal science directly to community needs. The idea, first proposed by Athelstan Spilhaus of the University of Minnesota, found strong champions in Knauss and Rhode Island Senator Claiborne Pell.

“It found fertile soil in Rhode Island, where we believed we were already doing much of what Spilhaus was proposing,” Knauss later reflected in GSO’s Maritimes, published in 2000. “The Sea Grant Act was passed in 1966. URI received one of the first grants in 1968 and became one of the first four Sea Grant Colleges in 1972.”

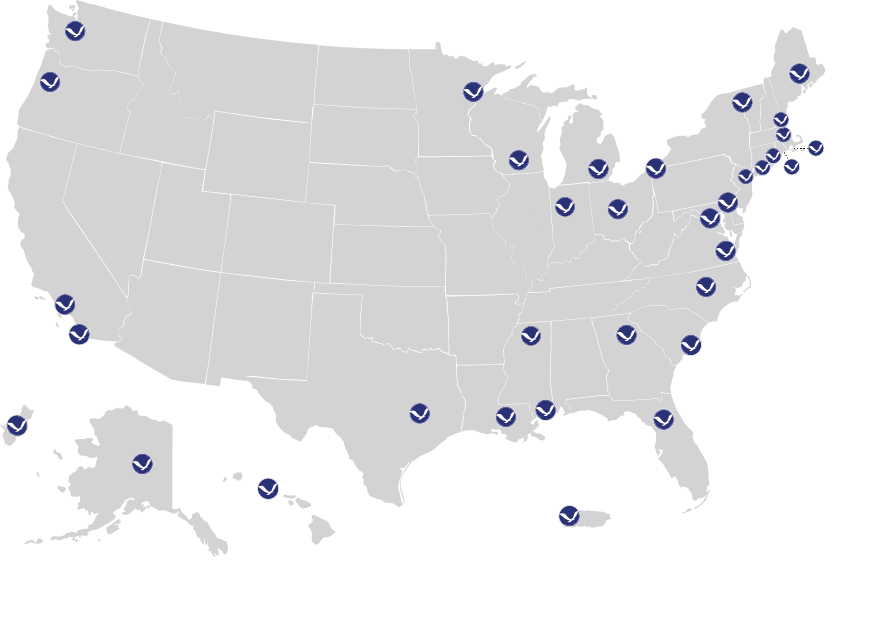

From those beginnings, Sea Grant has expanded to 34 programs in every coastal and Great Lakes state, as well as Puerto Rico and Guam. Today, it helps communities adapt to coastal hazards, build resilient economies, and preserve sustainable resources and ecosystems for future generations.

Knauss serving on a panel with colleagues at the first Sea Grant Conference, held in 1965 in Newport, R.I. The panel members are discussing possibilities and complications of Sea Grant from a university’s point of view.

Knauss foresaw the challenges the ocean would face in the 21st century.

“I believe the oceans and the 70 percent of the Earth that is underwater will play an increasingly important role in providing a variety of resources, including energy and fresh water, to an increasing population. Perhaps even more important is that environmental stresses will also grow in the next century,” he said in Maritimes. “Many of these issues concern the ocean and our need to better understand its role: changing sea level, coastal pollution, modifying the earth’s climate, maintaining the current atmospheric chemical balance, and much more.”

Knauss’ vision is also carried forward through the John A. Knauss Marine Policy Fellowship, established in 1979.

This prestigious fellowship provides graduate students with a year in Washington, D.C., working on marine and coastal policy in either legislative or executive offices. For many, it has been the launching point for careers in science policy and leadership.

“The Knauss fellowship is the clearest pathway to make or explore the transition into policy,” said Cynthia Suchman, Ph.D. ’98, who served as a Knauss Fellow in 1999. She credits her experiences at GSO and as a fellow with guiding her toward her work with the National Science Foundation.

Over his career, Knauss became one of the foremost leaders in both oceanography and marine policy. He served as Under Secretary for Oceans and Atmosphere in the Department of Commerce, Administrator of NOAA from 1989 to 1993, president of the American Geophysical Union, and a delegate to the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea.

While the ocean has often seemed vast and untouchable—with roughly 80% still unexplored—advances in science and technology continue to highlight its direct connections to human life. Knauss understood this, and his legacy in ocean science, education, and policy has transformed the careers of thousands across the country over the last four decades.

Knauss passed away in 2015, but his vision endures as Senator Sheldon Whitehouse (D-RI) reflected:

“He was a remarkable man who has done a lot for Rhode Island and our oceans industry. Sea Grant … owes an enormous amount to [former] Rhode Island Senator Claiborne Pell and [former] Graduate School of Oceanography head and [NOAA] administrator, John Knauss.”

On what would have been his 100th birthday, we remember Dr. John A. Knauss as both a Rhode Islander and a national leader—one who understood that the ocean, vast and complex, is inseparable from the future of society itself.

The Enduring Legacy of John Knauss

Sept. 6, 2025

Narragansett Bay Campus

– Meredith Haas, RISG Science Communications & Digital Strategy Lead